Effective dialogue

A skill that every trainer should possess, especially those leading significant change, is the ability to engage others in dialogue. The trainer who can create a safe space in which open, and honest communication is practiced, ultimately creates a cohesive group of increased trust, understanding, and shared meaning.

An effective dialogue can be a pool of emotions, which can collectively heighten the confusion and the anxiety, and it works both ways. A trainer’s capacity to manage conflicting states of participants’ response, equips individuals and groups with the confidence to tackle difficult issues and to deal with constructive change in the future.

It is a method developed by Katherine Tyler Scott. By using this method, we are reaching high levels to:

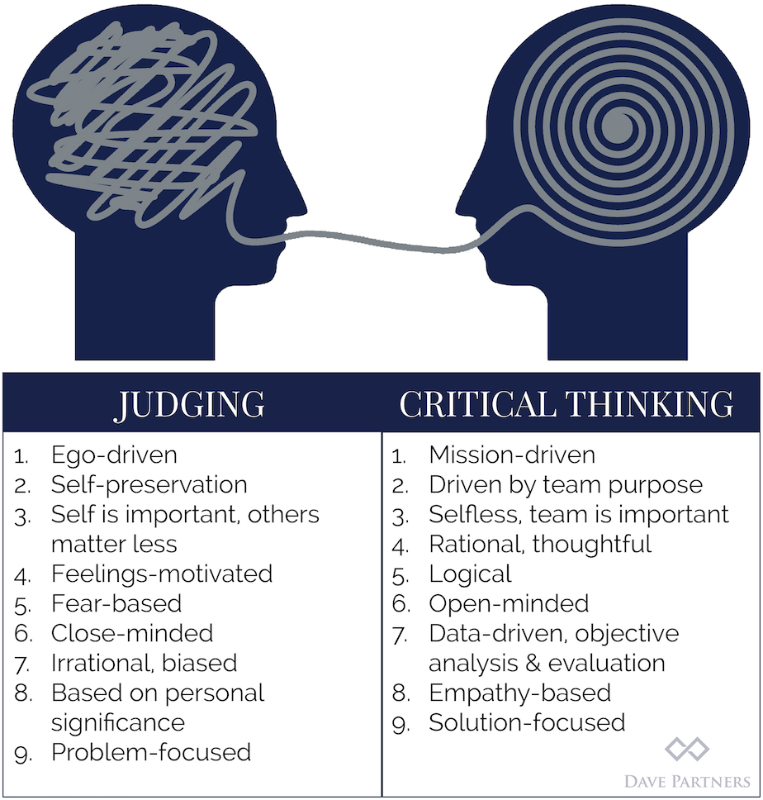

- think critically – the skill to explore, review and question everything in a critical way

-

- respect and use the diversity of opinions – by providing space for dialog and reflection

- support learners in developing their sense of civic engagement – by consciously using the group and training course`s environment to develop their sense of civic engagement

- be aware of the importance of not being judgmental about learners` values and beliefs and to listen in a nonjudgmental – yet responsible manner.

Description:

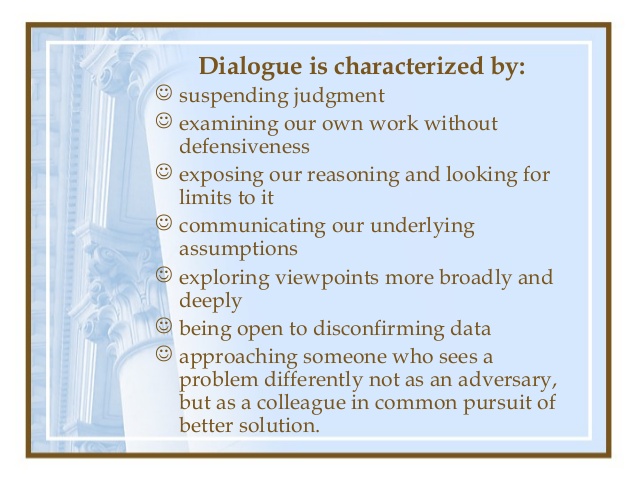

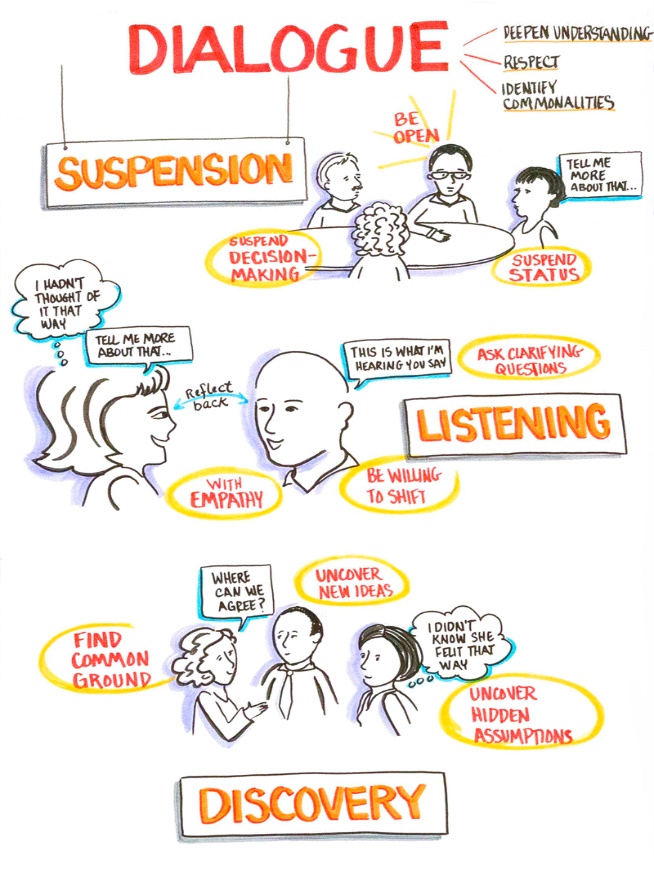

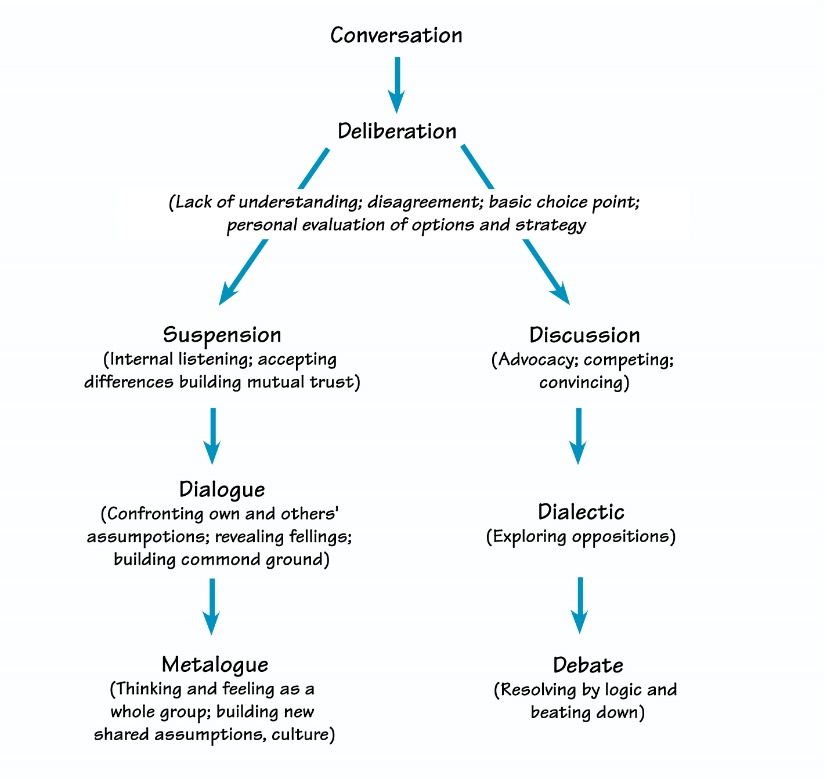

Dialogue is a form of conversation where people genuinely try to access different perspectives to enable a new understanding to emerge. Unlike debate, dialogue seeks to discover a new meaning that was not previously held by any of the participants in the dialogue. While difficult to achieve, the seven skills of dialogue can be practiced at any time. Through practice, dialogue skills can significantly enhance a discussion.

Building the Foundation for Dialogue

What is dialogue? The word “dialogue” comes from the two Greek words: dia, meaning “through”, and logos, interpreted as “word” or “meaning”. To engage in a dialogue is to engage in making meaning. In order to have effective dialogue, Katherine Tyler Scott proposes these four elements:

- Equality of participation. Dialogue recognizes the nature of human beings and their different perceptions, assumptions, and opinions that they bring to any given issue. Group norms or ground rules are necessary, and they must include treating every person’s perspective with respect.Each person has a voice and their voice is heard and equally valued. Top-down structures of relationship and communication that exist externally among members in a group are non-existent in dialogue.

- No threat of judgment, pressure or persuasion, is allowed and no one’s opinion “trumps” another’s. Title, position, and rank are not permitted to influence how individual ideas and options are received.

- No opinion outcome. There are no outcomes or decisions towards whether the group is steered or manipulated.

- Open agenda. The agenda is not hidden, and the only purpose of convening the group is to engage in authentic communication.

Making sure the elements above are present, is the first step that will help open and manage the effective dialogue. The other crucial piece to successful dialogue is through using the seven skills of dialogue, which are: deep listening, respecting others, inquiry, voicing openly, balancing advocacy and inquiry, suspending assumptions & judgements and reflecting. Each skill is explained below.

Deep Listening

Deep listening skills represent the ability of the participants to listen deeply, in order to understand and make connections, and not just imperceptibly hear the other person’s words.

To truly listen, means you attend to, follow and reflect upon what is being said by others.

- Attending: Ninety-three percent of what we “hear” in communication is nonverbal! Attending demonstrates that the listener is physically involved in hearing what a speaker is saying. Paying attention to the physical body, posture and movement, tone of voice, eye contact, and other nonverbal cues will provide the listener with considerably more information.Attending is a genuine intent to understand the other person. Inauthentic leaders are transparent in this respect. Healthy groups can read the nonverbal level when the leader is being dishonest, reticent, or manipulative. Even when a group cannot articulate this, they know that there is dissonance between the leader’s intent and impact. Groups can sense a disconnect between what is being said and what is being done. Such behavior undermines the development of trust that is essential for dialogue and healthy group development. Examples of authentic attending skills are: nodding of the head, sitting up and leaning toward the individual speaking, good eye contact, and being focused yet relaxed.

- Following: This skill involves being appropriately and actively silent and allowing the silence to be “the mother of the wisest thoughts.” The speaker uses language that invites more exploring and learning, which opens the space for inquiry. Examples of this skill are open-ended questions and “I hear you” responses used in a reasonable, non-rote and genuine manner.

- Reflecting: This skill involves carefully listening and then integrating what was heard and rephrasing in your own words, the content and the feeling conveyed by the speaker. The listener reads at multiple levels and verbally communicates what they understand the speaker is saying. This enables the speaker to affirm or correct the listener’s understanding.

Deep listening increases individual and group capacity to be empathic toward others. It lessens defensiveness and paves the way to more freely exploring one’s own and other perceptions, assumptions, and opinions. At this point and this point only, is true learning possible. Not until participants can expose the underlying assumptions that construct their own views, are any changes of substance and sustainability possible.

Respecting others

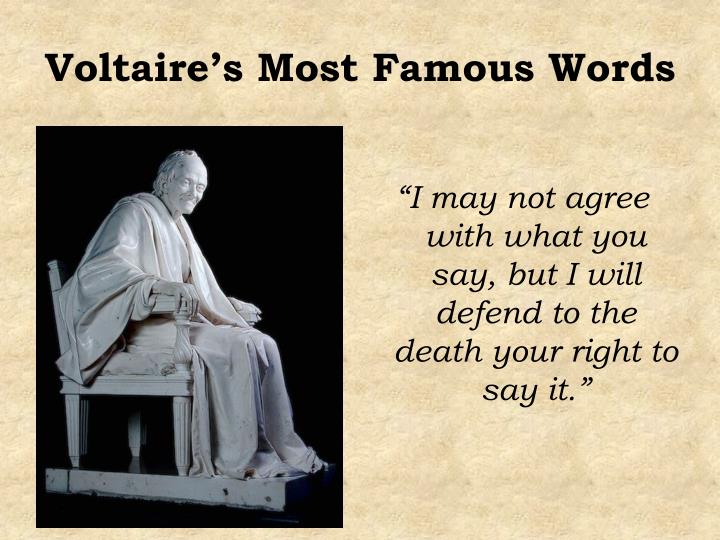

Voltaire, a French author, humanist, rationalist and satirist has reportedly said, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” This perspective lies at the heart of respecting others. Clearly this is particularly difficult to do when we interact with people who have contrasting views to our own. Practicing this dialogue skill, therefore, becomes imperative if we are to develop the true capacity to dialogue. While respecting others does not mean that you have to agree with them, it does mean that you will allow them the time and space to have their say. Then you will see it as a perspective that while you may not understand it, is a perspective that is valid in the context that it contributes, even if only in a small way, to our understanding of the ‘complete’ picture of whatever is our area of focus at the time.

Inquiry

This is the capacity to ask genuine questions. As such, it encourages the use of open questions that enhance our understanding of different perspectives or assist in the deeply held mental models that lie behind many perspectives to come to the surface.

Voicing openly (advocacy)

Many of us are quite talented in this skill, at least partially. Voicing openly is the capacity to say what you think and to be able to explain why you think that. Unfortunately, many people struggle to share their views. All views, if they exist, are important for the development of a true understanding of a situation. If those views are not shared, then a part of the picture is missing which is why voicing is so important in the context of dialogue.

Suspending assumptions & judgments

The capacity to explain why we hold the views that we hold lies at the heart of suspending assumptions & judgments. Much like we hang our clothes to dry, suspending means that we hang out our reasons for our views. This allows people to look at them, question them and assist us in developing a deeper understanding of our perspectives. To suspend your assumptions & judgments illustrates a willingness to be vulnerable which is a key attribute of servant leaders. Should we discover that our views are not useful through the act of having suspended them before others, we could adopt new ones. This experience is often described as true learning.

Balancing voicing (advocacy) and inquiry

This is as simple and complex as balancing, sharing our view and why we have it with asking genuine questions to better understand another person’s view or to allow the group to talk about issues that will enhance the whole group’s collective understanding of a topic. To practice, this skill involves utilizing all the skills listed above deep listening, respecting others, inquiry, voicing openly and suspending assumptions & judgments. Even if other people with whom you are conversing are not trying to dialogue, practicing this skill significantly enhances the quality of your contribution to the conversation. People will notice your enhanced communication skills because the quality of the conversations within which you participate will be enhanced by your contributions to them.

Reflecting

Our fast-paced world offers little time to reflect. However, the capacity to reflect is a big rock and enhances our communication skills and the capacity to dialogue through considering how we have just practiced our skills. In team environments it is worth holding a reflection at the end of an attempted dialogue to recognize where the skills of dialogue were used effectively and where they could be improved.

Dialogue and Effective Change

When there is an opportunity to use all the deep listening skills and adhere to the established criteria for dialogue, a group will develop the trust and shared meaning necessary to engage in the adaptive work of change. Dialogue creates an environment and process for empathic examination; and doing the choice to change remains within the control of the individual rather than in the leader or from the pressure of groupthink. Underlying assumptions that contribute to miscommunication and conflict will be brought out and the parameters of the issues being addressed will be clear.

Too often, the tendency in a group dealing with change is to minimize the anxiety and tension by rushing into problem-solving and decision-making. Inevitably, listening suffers. Engaging in dialogue helps a group get clear about the issues, thoroughly hear the multiple perspectives, and lays the foundation for establishing effective communication, a strong relationship, and long-term trust. The sheer act of being listened to and understood without fear of retaliation, attack or judgment is healing for a group, especially one with a history of conflict or repression of differences. It takes leadership to use these skills and implement the ground rules and criteria for engaging in dialogue.

Dialogue is not a quick-fix approach; it is a process requiring thought, skill and effort. It is not a panacea for all that ails the performance of groups and organizations; it provides a solid foundation for the development of sustainable change. The most important variable for the successful exercise of dialogue is an effective leader, skilled in applying it to many situations.

Dialogue, on the other hand, is a basic process for building common understanding. By letting go of disagreement, a group gradually builds a shared set of meanings that make much higher levels of mutual understanding and creative thinking possible. As we listen to ourselves and others, we begin to see the subtleties of how each member thinks and expresses meanings. In this process, we do not strive to convince each other, but instead, try to build a common experience base that allows us to learn collectively. The more the group achieves such collective understanding, the easier it becomes to reach a decision, and the more likely it is that the decision will be implemented in the way the group meant it to be.

The facilitator has a choice about how much theoretical input to provide during accession. To determine what concepts to introduce when there is a map of the dialogue process based on Bill Isaacs’ model, which describes a conversation in terms of two basic paths — dialogue and discussion.

Why did I choose this tool?

We clearly need ways of improving our thought processes, especially in groups where finding a solution depends on people reaching a common formulation of the problem. Dialogue, a discipline for collective learning and inquiry, can provide means for developing such shared understanding. Proponents of dialogue claim that it can help groups reach higher levels of consciousness, and thus to become more creative and effective. The uninitiated, however, may view dialogue as just one more oversold communication technology.

The effectiveness of the dialog by Katherine Tyler Scott, I find very useful when leading training. It has helped me not only to teach the participants but to listen to them, develop trust and build understanding. The steps of attending/following/reflecting are present in every session, group discussions and the whole training in general.

I believe that in addition to enhancing communication, dialogue holds considerable promise as a problem-formulation and problem-solving philosophy and technology.

Suggested Reflection Questions

What are the consequences of effective dialog?

Will you try to listen more?

Can you be aware of the direction of the dialog?

Other Ways to Practice

- Increase trust.

- Achieve mutual understanding before engaging in decision making.

- Deal with emotion-laden, potentially divisive content.

- Manage diverse opinions about a topic or issue.

- Determine shared interests and establish common ground.

- Create new ways of seeing and doing things.

- Develop cohesiveness and community.

- Make the members feel as equal as possible. Having the group sit in a circle, neutralizes rank or status differences in the group, and conveys the sense that each person’s unique contribution is of equal value.

- Give everyone a sense of guaranteed “air time” to establish their identity in the group. Asking everyone to comment ensures that all participants have a turn. In larger groups, not everyone may choose to speak, but each person has the opportunity to do so, and the expectation is that the group will take whatever time is necessary for that to happen.

- Set the task for the group. The group should understand that they have come together to explore the dialogue process and gain some understanding of it, not to make a decision or solve an external problem.

- Legitimize personal experiences. Early in the group’s life, members will primarily be concerned about themselves and their own feelings; hence, legitimizing personal experiences and drawing on these experiences is a good way to begin.

The role of the facilitator can include the following activities:

- Organize the physical space to be as close to a circle as possible. Whether or not people are seated at a table or tables is not as important as the sense of equality that comes from sitting in a circle.

- Introduce the general concept of dialogue, then ask everyone to think about an experience of dialogue (in the sense of “good communication”).

- Ask people to share with their neighbor what the experience was and to think about the characteristics of that experience.

- Ask group members to share what aspects of such past experiences made for good communication and write these characteristics on a flip chart.

- Ask the group to reflect on these characteristics by having each person (take) in turn(and) talk about his/her reactions.

- Let the conversation flow naturally once everyone has commented (this requires one-and-a-half to two hours or more).

- Intervene as necessary to clarify, using concepts and data that illustrate the problems of communication.

- Close the session by asking everyone to comment in whatever way they choose.

Exercises:

You can find exercises at the end of this article.

Here is one more that can be useful:

Recreate a dialog

- Find a film clip that includes a bad dialogue.

- Put the students into pairs and show the scene to the class. If possible, provide each team with a transcript of the scene.

- Give the pairs time to rewrite the dialogue in their words.

- Have each team perform their dialogue for the class.

- Learn from the different perspectives and understand the meaning behind the words

Bill Isaacs describes the need to build a container for dialogue—to create a climate and a set of explicit or implicit norms that permit people to handle “hot issues” without getting burned (see “Dialogue: The Power of Collective Thinking,” April 1993). For example, steelworkers participating in a recent labor/management dialogue likened the dialogue process to a steel mill in which molten metal was poured from a container into various molds safely, while human operators were close by. Similarly, the dialogue container is jointly created, and then permits high levels of emotionality and tension without anyone getting “burned.” The facilitator contributes to this by modeling behavior—by being non-judgmental and displaying the ability to suspend his or her own categories and judgments. This skill becomes especially relevant in group situations where conflict heats up to the point where it threatens to spill out of the container. At that point, the facilitator can simply legitimize the situation by acknowledging the conflict as real and as something to be viewed by all the members, without judgment or recrimination or even a need to do anything about it.